The first county-run poor farm in Minnesota was instituted in 1854 in Ramsey County on land acquired by the County Commissioners. Apart from military forts, the only existing residential institution then in the Minnesota Territory era was the Stillwater Prison, built in just the previous year, 1853. This means that Minnesota’s first poor farm, the Ramsey County Poor Farm, predated jails, hospitals, orphanages, reformatoriums or sanitoriums — and of course, the founding of the State of Minnesota itself.

It seems to me a fairly good hypothesis that the situation of hungry, elderly, ill, disabled, and newly arrived poor settlers in the late-colonial frontier must have left a powerful and lasting impression on early settler governments. We don’t just find this local anti-poverty relief system in the large and long-running Poor Farms in Ramsey, Hennepin or Saint Louis Counties, but also in remote counties and counties with smaller populations. In almost all cases, counties would run poor farms rather than townships. As compared to even the quickly growing and industrial towns, county administration offered institutional advantages for more flexible budgeting and supervision, as well as more options for land acquisition. There was great variation in both the size of a poor farm and its location in relation to other sites in a community. Changes to the size and location of a particular poor farm were also common.

While the Minnesota legislature developed pertinent poor laws in the 1860s, there was no state-level system to regulate county poor farms until the State Board of Control of Corrections and Charities was founded in 1883. In short, while this is an institution that spoke to historical currents and deep contradictions throughout the US, each poor farm crystallized on the ground a bit differently.

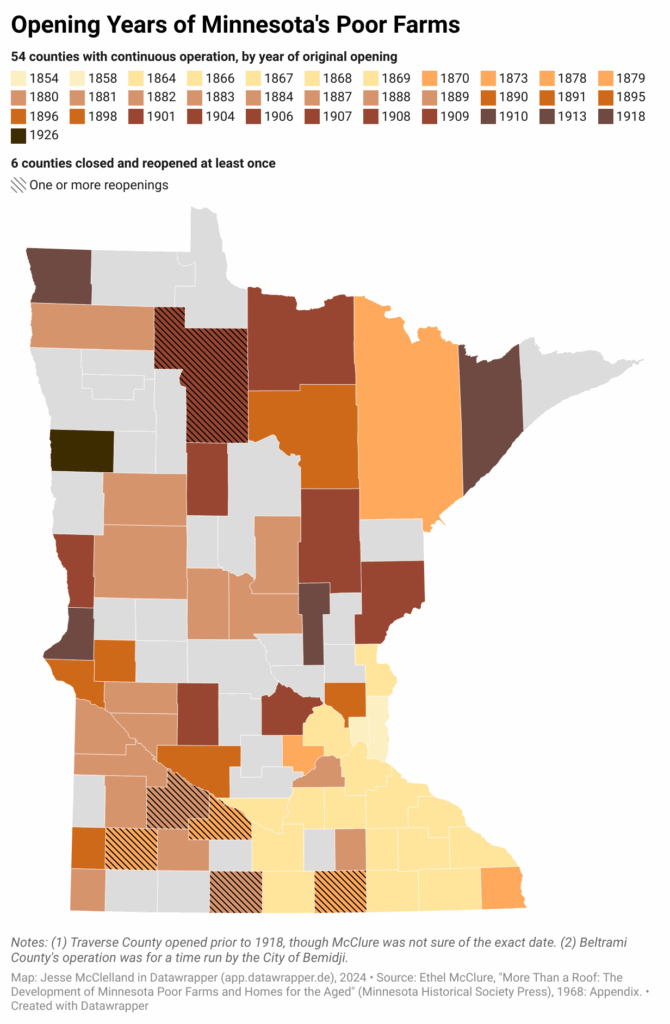

To illustrate the spread of poor farms, I created this map based on the findings of the public health expert, Ethel McClure. Her excellent book, More Than a Roof: The Development of Minnesota Poor Farms and Homes for the Aged, notes 60 counties in Minnesota that ran poor farms at one time or another. Some of these operations closed and reopened once or more. McClure recognized that Norman County Poor Farm was the very last to open in Minnesota, in 1926.

Following the federalization of welfare in the New Deal era, the spatial logic of concentrating poor and otherwise vulnerable people in county-run residential institutions no longer held up. As elsewhere in the US, Minnesota’s counties sought to divest themselves from poor farms in the 1940s and 1950s. Residents — often called “inmates” or “paupers” — were transferred to other sorts of institutions, or were presumed to have better outcomes on their own with Social Security at some other residence.

Already by the time of McClure’s research in the 1960s, the land and infrastructures of former county poor farms had been repurposed. Counties turned to clinics or eldercare facilities instead. Through county sales and leasing of land, poor farms often gave way to private farms, homes and boarding houses. Some counties have embraced preservation of key infrastructures, but often preservation of poor farm cemeteries happens at the initiative of local volunteers.

The range of poor farm legacies makes it difficult to tell simple stories about the goodness or the badness of poor farms, or to find a cautionary moral tale, or to see if they might spark new approaches to care or housing. There is an even simpler issue at play. With county poor farm grounds fragmented, erased, overgrown, or concealed behind private fences, poor farms are nearly ubiquitous, but easily overlooked. Since we do not hear much about them and do not see them, we have little reason to be curious about them.

A postscript on McClure’s work

The Minnesota Historical Society published McClure’s book in 1968. Today, the Gale Family Library at the Minnesota History Center in Saint Paul maintains many of McClure’s papers. From what I can tell, she developed a meticulous filing system, organized by county. She created neatly printed 2-page surveys that featured handwritten responses by hospital and nursing home managers, as well as brochures from many of the new public and private eldercare institutions. She also kept typed and hand-written notes from her interviews and meetings with local experts and managers.