More than 10,000 people lived on poor farms in Minnesota at some time or other. At least this is my own estimate, a conservative one. While particular poor farms throughout the US often had small residential populations, they were nonetheless common. Many families today in the US might be surprised to learn that they could trace their own relations to them. But such insights would likely hinge on the availability of primary data sources such as Inmate Registries/Log Books, Death Certificates, or Census records.

To emphasize the dignity and autonomy of the people who resided in poor farms, a goal of this project is to take up the experiences of particular residents as far as primary sources can allow. This is something I hope to do in several stages and through different data sources. Records were kept in these Registries to support institutional mandates more so than the inmates themselves. But they can offer us rare glimpses into the life courses of individual poor farm residents.

I take the position that maintaining historical records on marginalized populations – while offering some contextual notes on the conditions of production and maintenance of such archives, as I am trying to do here – is an ethical imperative. Inmate Registries might be some of the only remaining written testaments of some peoples’ lives. For all the counties across Minnesota with poor farms, one of the things that makes Ramsey a bit unique is that it is one of few for which decades of Inmate Registries still exist today. There is value in recognizing each individual name.

What were the Inmate Registries?

The only Inmate Registries from the Ramsey County Almshouse that I know to still exist today are in two thick, hardbound ledgers. They sit in the special collections stacks at the Gale Family Library at the Minnesota History Center. Specially titled columns and numbered rows track the years of 1913 to 1915 in one ledger and 1916 to 1944 in the other. Since residents appear in these Inmate Registries alphabetically by last name, we know that their data were actually compiled after the fact from other Registries that would have been developed in chronological order.*

Logging basic data on residents through Inmate Registries would have been a common aspect of poor farm administration across most counties throughout the US. Even this rudimentary data collection was probably a best practice of administration, whereas in many counties, poor farms were run in a more customary mode. For the larger poor farms, such as Ramsey County, this was certainly a cheap and easily maintained strategy of record keeping and it would have enabled periodic reporting on operations and budgets. There may have been other reasons for such record keeping, too.

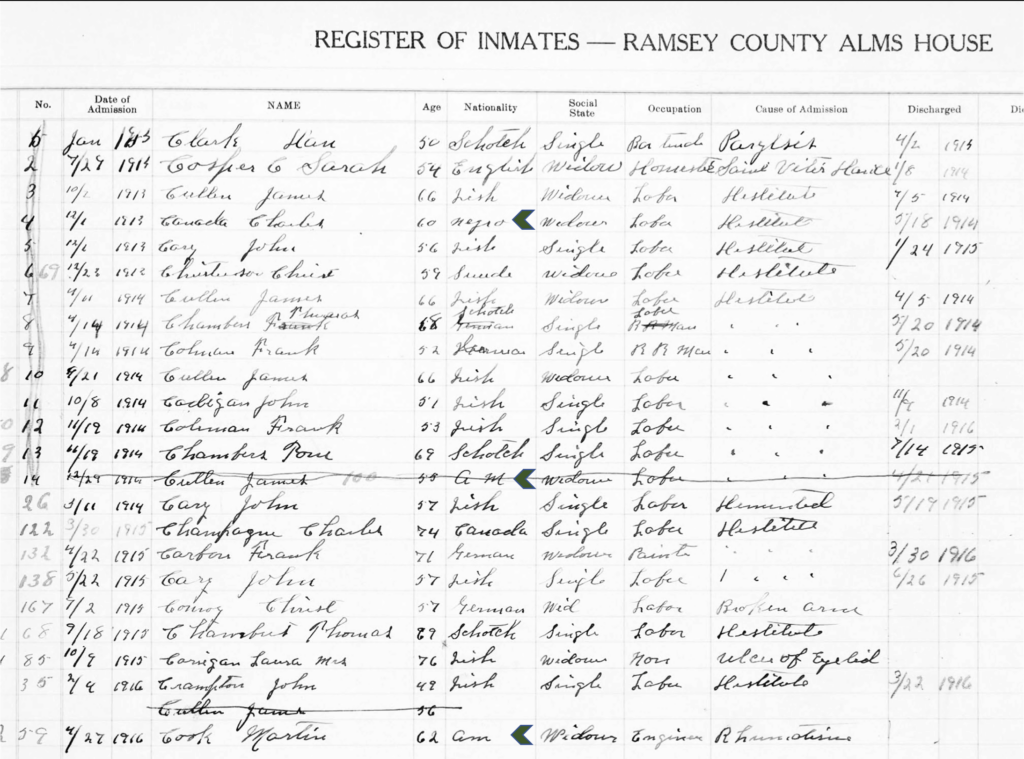

Entries for each individual in the Inmate Registries were made on the following categories:

- No. [suggesting chronological order within each ledger, though incomplete]

- Date of Admission

- Name

- Age

- Nationality

- Social State [var. Single, Married, Widowed]

- Occupation

- Cause of Admission

- Date Discharged or Died [date given for one of these columns or the other; no cause listed in either column]

- REMARKS

There are also additional notations on the page outside of these columns. These might be cross-referenced notes of the alphabetical (original) Inmate Registries done over many years to the chronological (compiled). I believe the Registries that we have today were probably done in a short span of time as the poor farm was closed.

Transcription of the Inmate Registries is slow and painstaking. For the time being, until the full Inmate Registries can be presented in typed and word-searchable form, some general trends are clear enough to share.

How many were at Ramsey County?

Over 90 years of operation and across four different sites, thousands lived at this particular poor farm. During the Great Depression, there was a national wave of new arrivals across the locally run poor farms and poorhouses. The Ramsey County Poor Farm probably hit its highest residential population in that era. For example, Boulay (2000) showed that in 1937, there were 357 residents, which was more than twice the intended residential capacity.

What was the intake process like? How long did residents stay?

Residents either presented themselves to the poor farm or were referred by an agency or caretaker. The three-member Board of Control of the Almshouse and Hospital, which was founded in Ramsey County in 1872, wanted evidence that potential residents were unable to sustain themselves through paid work, or through support from their kin networks or some other institution. Entry criteria were formalized over time. A basic requirement was that residents in any of Minnesota’s poor farms needed to prove residency in a particular county for at least a year.

After admission, residents stayed at the poor farm for several days, a season, or many years. There was no particular attempt to rehabilitate poor farm residents, to train them for better farming to be done later upon discharge, or to place them out quickly to other institutions. Many entries in the Registry conclude with transfer to the Hospital or death at the poor farm. There is not much evidence to suggest that people were discouraged from approaching poor farms, though it is possible that there were stigmas and structural inequalities sufficient to keep many needy people from approaching them.

Why did residents come in the first place?

Only one “Cause of Admission” is entered in the Inmate Registries for each resident. Commonly listed causes include “rheumatism,” “heart disease” or simply, “destitute.” Such remarks are of course a small part of the causal chain. We know that residents coped with poverty, illness, disability, and old age. Many contended with a combination of these and other factors. For some, we can imagine that support from family may have been sufficient until a certain point in time forced a decision point. An emergency, such as the onset of illness or the incapacitation of a caregiver, might have been the sort of challenges that made application to the poor farm a reasoned, if complex, choice.

Age, health and bodily ability

Residents were a diverse population, but the Inmate Registries we have from the early 20th Century suggest several commonalities. Most notably, perhaps, is that residents are often listed entering in their sixties, seventies or eighties. However, some arrived in middle age. One person, entering as a double amputee, is listed in their twenties. If babies were born at this particular poor farm, they were not recorded in these Inmate Registries.

While notes on health and bodily ability figure in the Inmate Registries, they do little to explain much about everyday life. They say nothing about what sorts of work a resident would be expected to perform, or even if they could work. A clear majority of residents in the Inmate Registries were identified as male, with occupational remarks such as “Laborer” and “Farmer.” For the many women who also were at the poor farm, “Homemaker” was a very commonly listed occupation. While agrarian livelihoods were very common throughout the US in the 19th and early 20th Century, we cannot assume that inmates who resided here were from rural places or that they knew much about farming before their entry.

The open-endedness of “Nationality”

The most complex column of remarks in the Registries is for Nationality. This single column seems charged with three categorical distinctions – citizenship, of course, but also nativity, and race. Crucially, these appear to be flexibly invoked, depending on how the resident is understood. A resident is never represented in a combination of these three distinctions.

First, Nationality seems only to be used in a plain meaning in the Inmate Registries – citizenship – if this person is a white-presenting US national. In such cases, one is labeled “American” (or “Am.”). In other words, race is left implicit to the reader. The conflation of “American” with “white” fits the self-understanding of settler society, particularly given that government at both the state and federal level promoted the settlement of European-origin peoples in Minnesota in the second half of the 19th Century.

A second case arises when someone was white-presenting and also foreign-born, the Nationality column actually means something different – nativity – as in one’s birthplace outside of the US. We see only European countries listed, such as “German,” “Irish,” “Swedish,” and many others. One notation is for “Bulgarian.” It is plausible that at least a few European citizens were residing in Minnesota’s poor farms prior to naturalization in the US. But considering the expectation of county residency for a year and the sheer amount of entries listing so many European nationalities suggest that it was nativity, not citizenship or even ethnicity, being recorded.

Third, there are several times when the Nationality column only captures racial ascriptions. Dozens of residents are listed as “Negro” or “Colored,” with no mention of citizenship or nativity. For decades, the US Census Bureau produced statistical annexes on “Paupers in Almshouses” across the US. In these annexes, the Census lists the “Color” of Paupers first, followed by “Nativity.” So behind this differential in approaches to record-keeping within the Nationality column, we should ask, how often was there differential treatment or forms of discrimination at poor farms on the basis of race?

There is one additional dimension to this Nationality column – the possibility that Indigenous people resided in Ramsey County Almshouse. This was the case in other Minnesota counties {citation?} and in other US states. While it is possible that Minnesota’s poor farms included Dakota, Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk or other Indigenous or Métis people, no such remarks arise in these Registries for Ramsey County. The US Decennial Census would only begin counting Indigenous people in 1860, and then under the nomenclature of taxed/untaxed.

What the Nationality column suggests is that rather than taking remarks in any column about particular residents in the Inmate Registries at face value, we should be considering how workers and managers at poor farms collected and used resident data.

in the Nationality column. Most of the other notes refer to Nativity. Photo scan courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Interpreting archival traces

There are many critical questions to be raised here. Given the vagaries of the Inmate Registries, how accurate can a demographic sketch of poor farm residents be? The conditions around the creation of these primary records placed real limits on them. While data was collected on new residents on a regular and ongoing basis, we cannot be sure that these records offer a complete account of all residents. We also cannot know if the records were taken in an accurate and systematic manner. To what degree did the residents determine what was written about them? Might clerks have had reason to undercount or misrepresent characteristics in the ledgers? How often did they make mistakes? Why cross a name off the list?

There are still some very compelling reasons to push ahead with the practical work of transcription, even with these ethical and political concerns in mind. First, a simple database of the Inmate Registries will enable demographic sketches of residents so that trends and correlations may emerge. Second, having arrived at names of particular individuals, a basis for comparison to other archival records would be enhanced. This may be of particular interest to genealogical researchers. Third, we might learn more about how time on the poor farm correlated with life circumstances and dimensions of life in broader society, such as health, labor and poverty.

*A massive records inventory of Ramsey County was conducted by the Minnesota WPA while the Poor Farm was still in operation. They noted earlier Inmate Registries dating back to 1868. While I hope that some version of these much older Registries still exist today, my own inquiries to date lead me to believe that they are not currently available at the Minnesota Historical Society. The records survey is at least available:

MINNESOTA WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION: An Inventory of Its Writers Project Research Notes for the Historical Records Survey at the Minnesota Historical Society See BC8.1.W956; Box 253.

Works Cited

Bakeman, Mary (1998) Ramsey County’s Forgotten Cemetery Park Genealogical Books.

Birk, Megan (2022) The Fundamental Institution: Poverty, Social Welfare and Agriculture in American Poor Farms Champaign: University of Indiana Press.

Boulay, Pete (2000) A Roof Over Their Heads: The History of the Old Ramsey County ‘Poor Farm’ Ramsey County History 35(2): 13-19.